With a fossil record that dates back to the Triassic period, and a human record predating 900 A.D, there’s nothing bite-sized about Santa Fe history. Though it’s tough to abbreviate such a rich and complex past, I have rummaged through time to post a brief-ish trek, beginning just prior to the arrival of the Spanish and leading up to the birth of the state.

1050-1607: Native Americans occupied the region. A small group of village dwellings were located around what is now known as the Historic Plaza area. The village was then known as ‘Ogap’oge, said to mean Olivella Water Place. Olivella is a shell originating in Mexico and the Gulf of California. It was traded among the ancient Native tribes and eventually found its way to New Mexico. It was used primarily for ornamentation in jewelry and crafts.

1540: Spanish Conquistador Don Francisco Vasquez de Coronado arrived by way of Mexico in search of the fabled Cibola, or Seven Cities of Gold. He claimed the area as the “Kingdom of New Mexico,” a part of the larger empire known as New Spain.

Drawn map of Kingdom of New Mexico in New Spain, by Jose Antonio de Alzate y Ramirez circa 1760. It also shows the Native Tribal Territories.

1598: Don Juan de Oñate established the capital of the “Kingdom” to be Ohkay Owingeh (Place of the Strong People), the Tewa village 25 miles north of Santa Fe.

The village was renamed San Juan Pueblo. (Quite recently, in 2005, the name was officially returned to the original Tewa, Ohkay Owingeh.) In 1598, there were approximately 40,000 Indians in the region. Even though there was little resistance, Oñate instilled fear by killing, mutilating, and enslaving hundreds of the Native people.

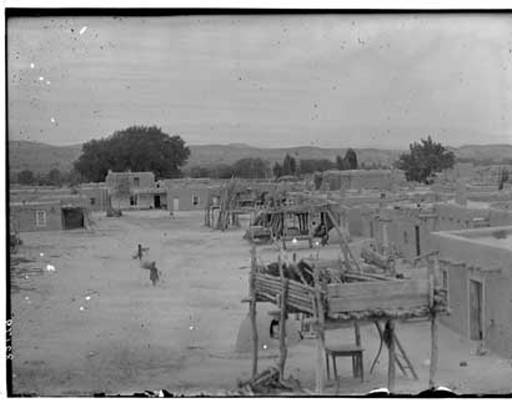

Main Plaza of San Juan Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh, photographed in the early 1900s, Courtesy of Palace of the Governors photo archives.

1607: The Spanish worked to colonize the indigenous people. Priests and officials attempted to obliterate the traditions, ceremonies, and beliefs of the ancient Native culture.

1609: Don Pedro de Peralta was appointed Governor-General. He founded a new city at the foot of the Sangre de Cristos, and called it “La Villa Real de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asis,” the Royal Town of the Holy Faith of Saint Francis of Assisi. It’s now known as Santa Fe.

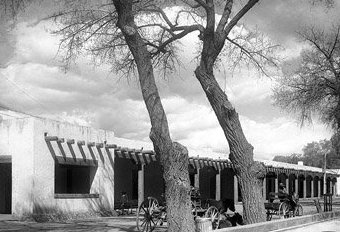

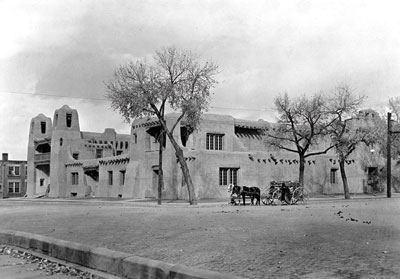

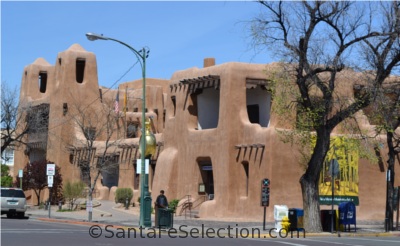

1610: Peralta made La Villa Real de Santa Fe the capital of the province. Between 1610 and 1618, construction of The Palace of the Governors began.

1670s: Drought caused famine, and the ongoing colonization efforts by the Spanish caused unrest among the Native people.

1675: Juan Francisco Treviño was Governor. He ordered hundreds of Native religious effigies be collected and destroyed.

Example of Religious effigy: Zuni Kachina Doll, prize winner at the 2013 Indian Market by Bart Gasper.

Forty-seven Pueblo medicine men were arrested and sentenced to death for sorcery. The sentence was carried out on three men. Some were publicly whipped, one committed suicide, the rest were imprisoned.

Among them was important Ohkay Owingeh religious leader, Po’pay. The news of the capture spread to the Pueblo leaders. Seventy Native warriors marched to Governor Treviño’s headquarters and demanded release of the prisoners. The prisoners were released without fighting.

Po’pay moved to Taos Pueblo after his release, and over the next five years gathered the support of eleven other Pueblos to run the Spanish out of New Mexico.

1680: August 10th, Po’pay led the “Pueblo Revolt.”

The last stronghold of the Spanish was the Palace of the Governors, the one public building not destroyed in the fighting. (It is now the oldest public building in the U.S.)

The Indians diverted the Palace’s water supply and by late August, or early September, the Spanish retreated to El Paso del Norte, led by then New Mexico Governor Antonio de Otermin. Native warriors followed them, from a distance, all the way to the border to ensure they made their exit.

1681: November, Otermin tries to return and claim power. By January 1682, his attempts fail. He returns to El Paso. Pueblo Indians continued to occupy Santa Fe and worked hard to maintain footing against frequent invasion from the Comanche, Apache, and other nomadic tribes.

1692: Don Diego de Vargas arrived to claim his 1688 Spanish appointment as the new Governor of New Mexico. It was September 13th. His company comprised a light infantry, seven cannons and one Franciscan priest. He offered protection from invading forces, in exchange for the return to the Catholic faith by the Indians. The Indians reluctantly acquiesced. On September 14th, it was official. Don Diego de Vargas’ “peaceful” return of the Spanish is celebrated today. Every September, members of the Fiestas de Santa Fe re-enact the event at the Plaza.

1696: As the years ticked on, the Natives grew tired of the continued oppression imposed on their traditions. A second revolt was attempted by fourteen Pueblos. Bloodshed was abundant on both sides. This revolt was less organized than the first, and sporadic fighting dragged on over the course of the next four years.

Late 1690s: By this time, De Vargas had established secure hold of the region. The Spanish issued substantial land grants to the Pueblos, and appointed a public defender to protect Indians’ rights and represent them in Spanish courts. Franciscan priests lightened their efforts to eradicate Native traditions and religious ceremonies. A peaceful alliance formed between the Spanish, the Pueblo Indians, Apaches and Navajos. Comanches still raided the city at times.

For the next hundred years or so, Santa Fe’s municipality grew and prospered.

1821: Mexico gained independence from Spain. New Mexico became a province of Mexico and Santa Fe became the capital of New Mexico. The Spanish lifted their closed trading policy that only allowed trade between the British, French and Americans. Trade opened between Mexico and the U.S.

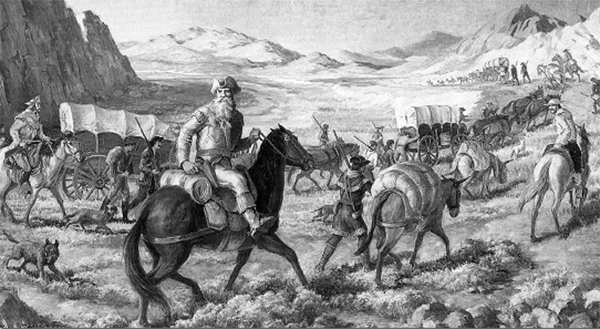

William Becknell started the 1,000 mile-long Santa Fe Trail, between Santa Fe and Missouri. More American settlers arrived.

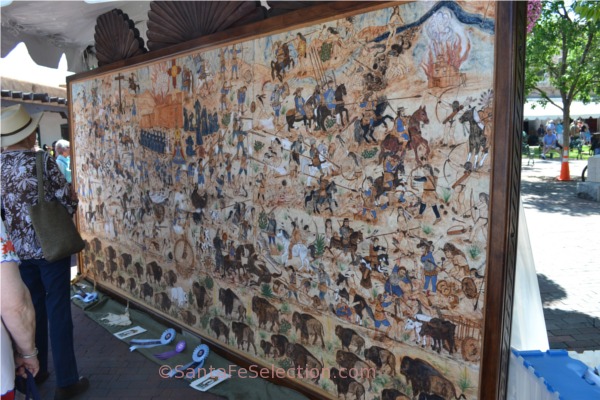

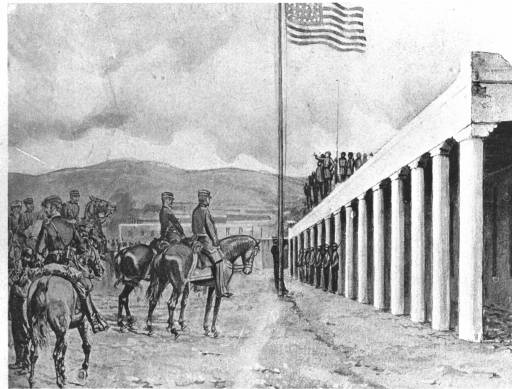

1846 : The Mexican-American War broke out. On August 18th, General Stephen Watts Kearny claimed Santa Fe, raising the American flag over the Plaza. (The Palace of the Governors had undergone some face-lifts and facade changes throughout the various governorships. The image below shows one of them.)

Raising the American Flag over the Palace of the Governors, Aug 18th, 1846. Photo of painting by Kenneth Chapman. Palace of Governors Photo Archives.

1848: New Mexico, Arizona and California were signed over to the U.S in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

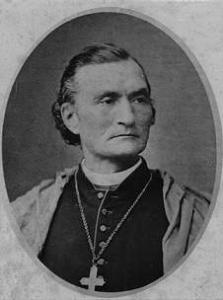

1850: French bishop Jean Baptiste Lamy was appointed Archbishop of the Santa Fe territory. Lamy caused a big shock to the Spanish when he decreed that all the Spanish religious carvings and effigies be removed from the Spanish parish church, La Parroquia. He replaced them with ceramic religious icons imported from France.

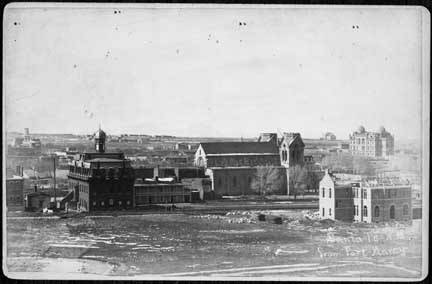

1870: Lamy began plans for building his dream cathedral. He chose the same site where a small mission church had stood until it burned down during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. The Spanish had replaced it with La Parroquia. Lamy replaced that with the St. Francis Cathedral. Lamy also commissioned the building of the first hospital in the area.

View of Santa Fe from Fort Marcy. St. Francis Cathedral in center. circa 1887. Image: Palace of Governors Photo Archives

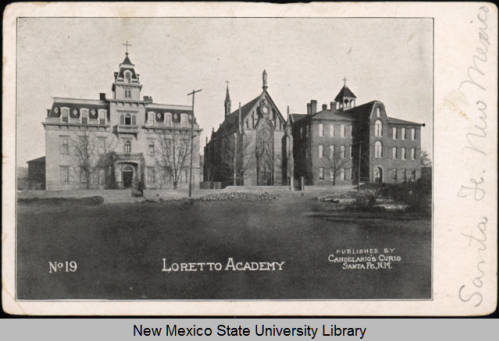

1873: Lamy encouraged the Sisters of Loretto to build the Loretto Chapel. See my blog article on the history of Loretto Chapel.

Loretto Academy buildings with Loretto Chapel in center, Santa Fe, ca 1909. Image: Palace of Governors Photo Archives

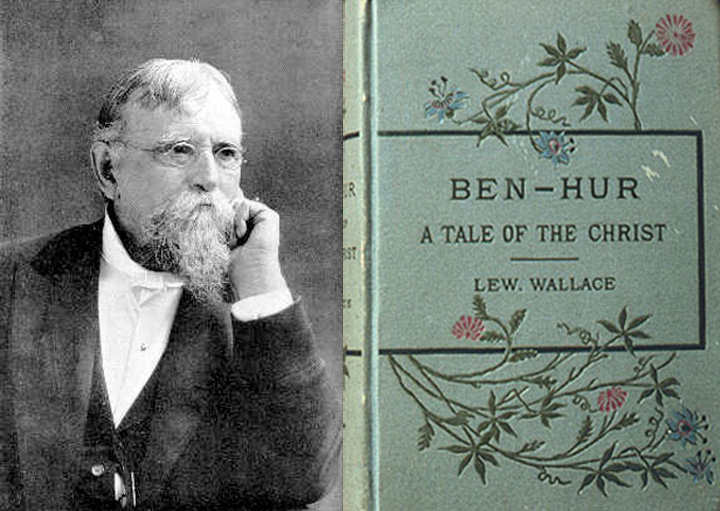

1878: Lew Wallace was appointed Governor. The Palace of the Governors was where he completed his well-known novel, Ben-Hur.

1880: The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad reached Santa Fe via a branch line from Lamy, a small town about 20 miles outside Santa Fe. Ranching boomed and so did the population, trading and tourism.

1889: A petition was received at Washington’s Capitol Hill asking that New Mexico not become a state under its own rule for fear of the local politicians being too corrupt.

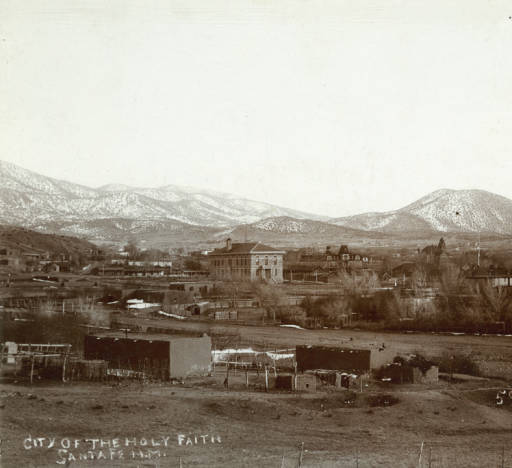

“City of The Holy Faith,” Santa Fe looking Southeast. Christian G Kaadt. circa 1895. Palace of Governors Photo Archives.

1909: The New Mexico Museum opened.

1912: January 6th, New Mexico became the 47th state. President Taft signs the Proclamation, saying, “Well, it is all over. I am glad to give you life. I hope you will be healthy.”

And that’s just the beginning! There’s a lot more fascinating history, but not for today’s blog.

One of the beautiful things about this area is the preservation and continual use of so many original historical buildings.

Palace of the Governors, 2014. The oldest public building in the U. S. And where Native American vendors sell their art and crafts every day.

The unique mix of varied architectural styles, from the earth-colored adobes, to the Territorial Revival themes, render a mystique of times past and stand beautifully defiant to current trends.

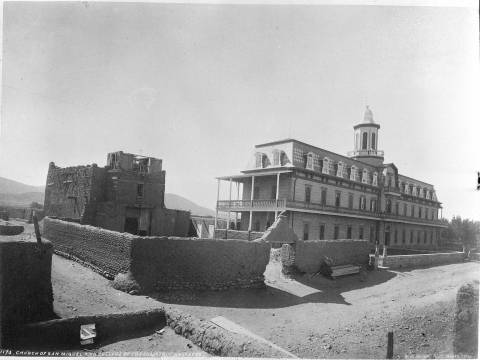

1881: San Miguel Church and St. Michaels’ School, Santa Fe, NM. Photo by W.H. Jackson and Co. Courtesy of the Palace of the Governors photo archives.

2014: The Oldest Church in the U.S. San Miguel Mission circa 1610. Badly damaged in the 1680 Revolt, rebuilt and restored many times. It sits alongside the original St. Michael’s School building, which now houses the Lamy Visitor’s Center.

I love that history is so important here. Diverse cultures proudly continue to honor their ancestors in a variety of ways. The Native cultures honor their traditions with religious feast days and ceremonial events throughout the year. One of the ways the Spanish heritage is honored is with Fiesta de Santa Fe, held every September on and around the Santa Fe Plaza.

If you’re visiting, there’s no substitute for a tour with a knowledgeable historian to delve deeper into Santa Fe’s fascinating stories, rumors, folklore and facts.

I recommend the walking tours around the historic Plaza area that leave from the New Mexico History Museum next to the Palace of the Governors, April through October, Mon-Sat at 10 am for $10.

It can be very interesting to chat to some of the locals, such as “Don Timoteo” Cordova, owner of local favorite restaurant Casa Chimayo. Don Timoteo is a direct descendent of the first Jaramillo and Archuleta families that arrived in the late 1500s and early 1600s. His restaurant is an original family home built in the early 1930s. He’s happy to tell guests of the Spanish history as passed down from his ancestors; just ask him. You can also go to pueblo villages and learn the Native perspective from some of the artists and locals. Cultural Treasures Tours with Robbie O’Neill offer a unique opportunity to meet Native American artists who have heard the history of their people as it has been passed down through generations.

At the state’s Visitor Center, in the Lamy Building that was once St. Michael’s School, on Old Santa Fe Trail, longtime local and historian Terry Tiedeman welcomes visitors with an excellent “Walk Through Turn of the Century Santa Fe” map to guide you to historical neighborhoods and buildings.

The area’s tumultuous history and the fact that many diverse cultures now, at last, peacefully co-exist here, is testament to how strong an affinity many folks feel for this radically different place. I felt it when I first arrived in 1984 – still do.

If you enjoyed this article, please sign up to receive my monthly posts via email. Thank you!

References

http://www.capitolreportnewmexico.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pueblo_Revolt