According to the calendar, October 31st through November 2nd sees a convergence of cultures in the Halloween and Día de Los Muertos celebrations. Over time, as more and more cultures have adopted variants of these two festivals, a few distinctions about their origins and meanings have become a little blurred.

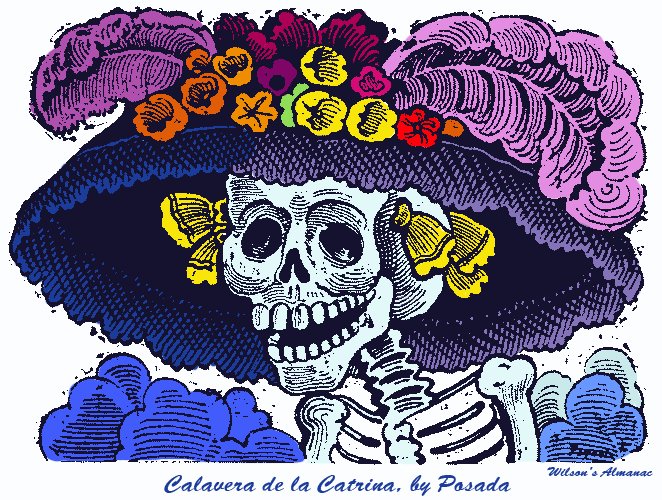

The Mexican El Día de los Muertos celebrations are said to trace back to the Aztecs as many as 3,000 years ago. From October 31st through November 2nd, the dearly departed are welcomed back for a visit to the hearts, minds and homes of the living. Death is considered a welcome guest during such celebrations. Often depicted by the skeleton La Catrina, death reminds us, with her toothy grin, to enjoy life while we can, seize the moment, and honor our ancestors that connect us to our cultural roots. Many costumes today are in representation of La Catrina, with the ornate death mask make-up.

A traditional altar or ofrendas is created in the home, and decorated with those essentials that help the dead on their journey between worlds. It’s a time of celebration – a time for joyful memories of the departed and how they touched our lives. Sharing stories with those who knew them and those who didn’t, makes their presence more strongly felt.

I recently visited a traditional altar in Casa Chimayo Restaurante. It honors owner Roberto Timoteo Cordova’s grandparents, Timoteo and Sophia. In the early 1930s, they built the adobe house that the restaurant occupies now.

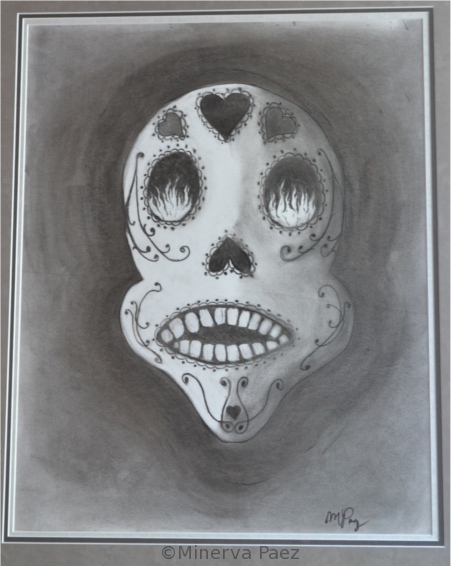

Roberto’s good friend Minerva created the altar according to the authentic Mexican traditions she learned as a child from her mother.

“Marigolds are the flowers used most,” she said. “They have a distinct, almost sour odor that is meant to catch the soul’s attention, and their brilliant colors are the lights that guide the dead to the altars that honor them. Salt is considered the essence of life, in Mexico, and is intended to rejuvenate them. Water is to quench their thirst after the long journey. And often a dish of the person’s favorite food is placed out for them on the actual day. The sugar skulls and ornately decorative make-up and costumes are a way of poking fun at the Grim Reaper. In a way, they say that death has no power over the bonds that connect us to those who are gone. It is a celebration of the lives of those who have passed on, and an appreciation for life by those who are still here.”

Minerva remembers the first time she attended a traditional Mexican Día de Los Muertos. “I was very, very young, maybe only four or five years old. My mother took me to Juarez to meet up with our relatives and visit the gravesites of our ancestors. It was a little scary for me at first, with all the skeleton imagery, but it actually became so amazing, so beautiful.

All the graves in the cemetery were beautifully decorated and there were so many people there. It was a vibrant place. At night, everyone lit candles and small bonfires, told stories, laughed, and played music. It was such a happy time. The celebration is an odd juxtaposition of happiness and sadness. But that first experience made a big, lasting impression on me.”

For centuries, and despite its spread across the globe into many diverse cultures, Día de los Muertos has maintained its traditional meaning.

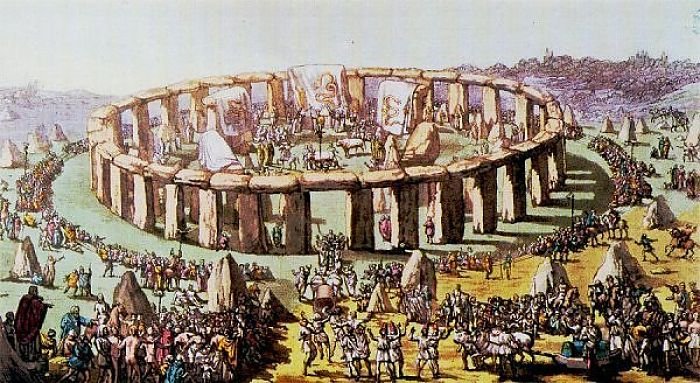

The origins of Halloween date back 2000 years to the ancient Celtic New Year’s harvest festival called Samhain (pronounced sow-in). November 1st marked the end of summer and the start of cold, short winter days. It was a time to harvest and prepare for adverse conditions. Superstition and fear were prevalent in the themes of the festivals.

To honor and appease the Celtic gods, they built sacred bonfires and gathered to burn sacrificial crops and animals. They wore costumes of animal heads, skins and skulls. It was a time for divination and attempts at predicting the future. It was also a time to appease and honor the gods, to ensure spring’s return as they felt the onset of the harsh winter season. The Celts believed that the eve of November 1st was when the veils between the living and dead were weaker, and ghosts returned to earth to wreak havoc by damaging crops and playing tricks.

Though factual records are scarce it is said offerings of food and wine were placed outside homes in an effort to distract the ghosts and prevent them from entering the house. It is also said that people didn’t go out after dark for fear the ghosts would attack them. To be safe, those who did venture outside wore ghastly masks in the hopes the ghosts wouldn’t notice the living were among them.

Over the centuries, many influences have brought variants to the original Druid tradition. In the first century A.D., the Romans invaded Britain, bringing their seasonal harvest tradition of worshipping Pomona, the goddess of fruit and vegetables with them. In the 8th century A.D., the Roman Catholic church declared November 1st the day to honor their saints. It was originally called All-hallows, or All-hallowmas, and later the church chose November 2nd as All Soul’s Day, to honor all dead. Over time, October 31st became the Celtic Samhain or harvest festival, and was known as All-hallows Eve, All Hallows E’en (short for ‘evening’) and subsequently Halloween.

In early America, colonial New England was the first area to celebrate Halloween. As more diverse ethnic groups arrived and people interacted with Native American harvest traditions, Halloween began to emerge as its own American identity.

It became a time of community, dancing, singing, telling fortunes and stories of the dead, ghosts and playing pranks. Even by the mid-1800s, the annual festival was not yet nationwide. A big shift happened when an influx of Irish immigrants fleeing the perils of the 1846 potato famine brought their Celtic influences with them.

It was then that Americans began adopting the tradition of dressing up in ghoulish costumes and knocking on neighbors’ doors asking for food or money, and “trick-or-treating” became common practice. By 1900, Halloween was more about community gatherings for all ages that included games, seasonal foods and festivities. Costume themes expanded beyond the gory ghosts and ghouls to include everything from movie stars to fairytale and comic book characters. After these changes, the religious and superstitious elements took a back seat.

Ronan The Destroyer, Rocket Racoon and Star Lord from Guardians of the Galaxy. Photo Courtesy of Mason Wagner and Jennifer Lang

So, whatever you’re up to this fall weekend, remember to enjoy yourself!! Here are a few of the fun events going on around Santa Fe to help you celebrate.

Oct 31st – Canyon Road Trick or Treating 4pm – 6pm. Cruise the galleries of historic Canyon Road. Kids in costumes get free treats at participating locales. Look for the Jack-O-Lanterns.

Oct 31st – Monster’s Ball at El Farol Restaurant and Cantina: Have a blast with live music from Girl’s Night Out Band, and costume prizes. $5 cover 8:30pm – 11:30pm

Oct 31st – Halloween BASH at The Cowgirl: Live music with Chango, Santa Fe’s favorite dance-band, 8:30pm – Midnight. Lots of fun! $5 cover.

Nov 1st – Museum of International Folk Art: Día de los Muertos 5pm -7pm. Create a community ofrenda (shrine or altar). Bring a picture or memento you do not need back to add your loved one to the altar. Mariachi music and refreshments. FREE event for all ages.

Nov 2nd – Museum of International Folk Art: Día de los Muertos 1pm – 4pm. Decorate sugar skulls, make memory boxes/muertos nichos, enjoy live music and Aztec dance and sample pan de muerto. Museum Admission. NM residents FREE every Sunday.

Here’s wishing you a safe and festive Día de Los Muertos, Halloween, All Saints Day from Santa Fe!!

Very, very interesting! Missing, however, was the tradition on the pueblo of “smoking” and offering up prayers of remembrance to one’s ancestors. We have been asked to one family’s ceremonies for many years. Don’t know if i feel honored or not with the skeleton’s name:Catrina!

HI “Catrina” / Kathryn, Thanks for your interesting addition. Please tell us more about that if you would.

Cheers!

Thanks for the Dia de los Muertos/Halloween primer. Well done!

thanks again , Maria , for a well-presented topical story !

Thanks for reading it, John. I’m glad you enjoyed it.

Best Wishes,

Maria